What Happened to the Refugee Students?

In one of my first postings, I mentioned volunteering at the Refugee School in Istanbul, a school staffed with volunteers who provide otherwise unavailable educational opportunities to refugee children in Istanbul.

In one of my first postings, I mentioned volunteering at the Refugee School in Istanbul, a school staffed with volunteers who provide otherwise unavailable educational opportunities to refugee children in Istanbul.The school is open to children ages 6-15, and this year students came from Iran, Iraq, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Ghana, Ukraine, Tanzania, Sudan, Somalia, and Sri Lanka. The school is a gift for these kids, who cannot attend Turkish school because they aren’t citizens. Twice a week, for 3 /12 hours, they receive lessons in English, Math, Music, Geography, Health, Art, PE and other subjects. Seven hours per week may not be much, but it makes a big difference. I spoke with one former student (one of my favorites) visiting from Ankara where he moved a few months ago and asked him how Ankara was. “It is bad,” he said. “We have nothing, no school.”

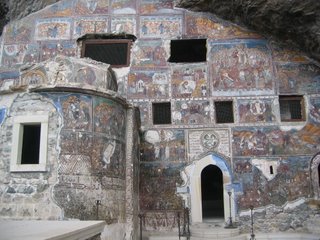

Attending and running a school under such uncertain circumstances is difficult at best. Each week brings a different group of children—attendance is often spotty. Furthermore, the school decided to close for a month in February and March following several attacks on clergy in Turkey. (The non-denominational school is located in a church.)

This is not a one-way education, as I have learned from these kids. We are currently working on a mural, with the original theme being “the future.” When brainstorming what they wanted in the future, the students gave answers that included satellite dishes, computers, big televisions, large houses and the like. At first this struck me as a rather materialistic theme for a mural. However, I learned that these children are often sleeping five to a bed under highly unstable circumstances. The big home with comforts familiar to many reading this blog represent both financial and psychological stability for these kids.

With changes to U.S. immigration policy likely in the future, I feel that it is a good time to draw attention to illegal immigrant children. (For an interesting article, click here.) To those who say that allowing illegal immigrant children to attend school in the U.S. encourages leeching off tax-payers’ resources, I would argue that for children who have little else in their lives, school is a necessary place for stability and growth, regardless of official status.